The final project for my Clio Wired class at George Mason University is a grant proposal for a new Digital History project. The generous and benevolent Professor Michael O’Malley has released a call for proposals, funding up to $500,000 for projects which use the internet, information technology, and the skills we learned in class to reach new audiences with historical information or resources. Given my recent scholarly and professional interest in Civil War photography, I have decided to propose a Civil War Photography Wiki database.

Abstract

The Civil War Photography Wiki will be a crowd-sourced database of photographs taken during the American Civil War era. The project’s goal will be to create this database online using existing tools and architecture, and then to encourage contributions from interested individuals and institutions, eventually culminating in a complete digital collection of all known photographs from the Civil War period.

Each record for a Civil War photograph will feature a high resolution digital image and metadata information of the type most relevant to scholars of the subject, including photographer, date taken, location taken, subject, process, provenance, current owner, and alternate versions. The site will be hosted on the servers of and maintained by the National Museum of American History, the Principal Investigator of this grant, but institutional partners will include the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution Archives, National Museum of African American History and Culture, and Center for Civil War Photography, among others.

The funds requested in the grant will primarily be used to launch the site and to encourage contributions and use among the community of enthusiasts and scholars who are its primary audience. The site will combine the tools and potential of internet technology and accessibility and transparency of online communities to foster a lively and authoritative community-centered base of knowledge to support and nurture research in this exciting field of history.

Project description

Historians frequently cite the American Civil War as a watershed moment in the history of photography and photojournalism. The war came some twenty years after the first photographs were taken in the United States following the unveiling of the Daguerreotype process to the world by its eponymous inventor, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre in 1839. By 1860, the United States had a burgeoning photography industry, with practitioners like Mathew Brady making small fortunes taking portrait photos at studios in major American cities and a smaller number of photographers venturing outdoors to make images of ceremonies, events, and notable places. Technological innovation, especially the invention of the wet collodion process, made photography cheaper, shutter speeds shorter, cameras and dark rooms more portable, and opened the practice to increasing numbers of artists and entrepreneurs who foresaw a growing market for images.

The Evacuation of Fort Sumter, 1861, albumen print from a photograph attributed to Alma Pelot. Metropolitan Museum of Art accession no. 2005.100.1174.13.

In the days following Major Robert Anderson’s surrender of Fort Sumter, Charleston photographer Alma Pelot rowed out to the fort with his camera and equipment to record the aftermath of the first major action of the Civil War. Mathew Brady, sensing a business and historical opportunity to make images of what many thought would be a brief war, was caught in the fighting and driven into the woods outside Bull Run with a sword to protect himself while attempting to photograph the battle. Throughout the war, photographers expanded the visual encyclopedia of their craft, capturing vivid portraits of military and political leaders, incredible photographs of the vast machinery of war, and haunting images of destruction and corpses on battlefields that shaped the public’s understanding of the war.

The famous photographs of the Civil War are essential to the public memory of the era in the United States. Newspapers reprinted photographs of battlefields and leaders, stereoview series brought the carnage of war into people’s parlors, and popular gallery exhibitions and books like Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War gave individuals a direct a realistic window on the fighting like no other medium had before.

Still, as with any historical event, as the years passed, Civil War-era photographs became scarce. In the decades following the Civil War, stereoviews, albums, cased photographs, and albumen prints were stashed away in attics, archives, bureau drawers, and antique shops while the photographers, publishers, and subjects of the photographs moved on and passed away, taking with them their knowledge about the works. A few notable examples remained in public imagination – many of the images from the era used in history textbooks and documentary series like Ken Burns’ popular The Civil War were reproduced from the large and relatively accessible institutions like the National Archives and the Library of Congress – but the vast majority of surviving Civil War photos are in private hands or archives physically accessible only to accredited researchers.

![Portrait of Abraham Lincoln by Alexander Gardner, Library of Congress Call no. LC-B812- 9773-X [P&P]. One of the most well-known Civil War photographs because of its accessibility in the Library of Congress collection.](https://ryanlintelman.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/lincoln.jpg?w=558)

Portrait of Abraham Lincoln by Alexander Gardner, Library of Congress Call no. LC-B812- 9773-X [P&P]. One of the most well-known Civil War photographs because of its accessibility in the Library of Congress collection.

The newly-abundant information, however, is dispersed, fragmentary, and often conflicting.

Attribution is a difficult and contested task, requiring one to have studied the work of many of the Civil War’s leading photographers and comparing photographs in multiple collections. Some members of the Civil War photograph community are experts at this task. Given their long careers poring over the works, many can visually and accurately identify the photographer of a particular piece within seconds, either from pure recall of similar works or reference to an exact copy in another collection. Too often, amateur or untrained individuals have attributed works to the best-known Civil War photographers, Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner, which have been positively identified in other collections as the work of more obscure practitioners.

As Metropolitan Museum of Art Photography Curator Jeff Rosenheim wrote in his recent exhibition catalogue Photography and the American Civil War, “The past quarter-century has been a dynamic period for everyone interested in the history of photography, especially of the American Civil War. Intense and often collaborative research has provided historians, independent scholars, collectors, dedicated amateurs, and members of the general public with frequent changes to the titles, image dates, and attributions for many of the thousands of photographs of the era.” [Jeff Rosenheim, Photography and the American Civil War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 3.]

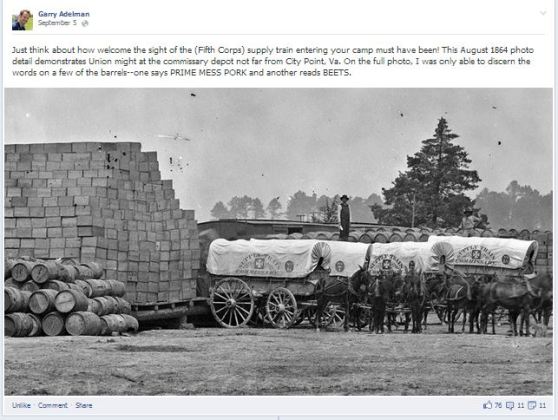

CCWP’s Garry Adelman has proven that the Civil War enthusiast community is willing and able to help professional historians uncover new details and help attribute maker, location, and date information for Civil War photographs like this one, posted on his facebook page.

Meanwhile, photo historians like the Center for Civil War Photography’s Garry Adelman have made careers out of their detailed explications and analyses of photographs from the Civil War period. In lectures, symposia, and lively discussion on his facebook page, Adelman zooms in, crops, and enhances high resolution images of glass plate negatives from the Library of Congress and other publicly available collections to uncover previously-overlooked details revealing much about the context of the photos and Civil War material culture. When enthusiasts and historians are given the ability to view these formerly inaccessible photographs in such high detail, their observations and discoveries, each colored by individuals’ particular expertise and life experiences and tempered in a crucible of positive discussion, are a model of crowdsourcing historical analysis.

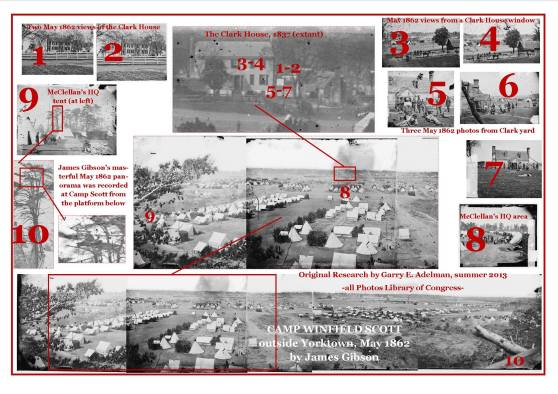

In one of the major successes of this new type of high resolution image analysis, Garry Adelman was able to prove that a well-known panoramic photograph at the Library of Congress was taken at Camp Winfield Scott, not Cumberland Landing, as had been previously recorded.

The community’s efforts to properly identify which photographs were made by which artists, in what order, and where, aids historians in understanding artistic intent, technological limitations and innovation, and photographers’ practices at a crucial point in the development of photojournalism and war photography. In a series of essays for the New York Times, documentary filmmaker Errol Morris recently proved the worth of this type of information about historic photographs. He attempted to resolve one of the enduring questions of photographic history: whether pioneering war photographer Roger Fenton staged his “Valley of the Shadow of Death” by moving cannonballs around a desolate road in the Crimea. The project hinged on Morris’ analysis of time of day and exact location of the photograph, the kind of information which information technology and the internet have given scholars the ability to determine and share with their colleagues.

The nonprofit education and advocacy group the Center for Civil War Photography has long sought funding and partners for a comprehensive digital archive of Civil War Photographs. This project, which has been postponed for lack of funding and partners, was intended “to digitally secure, preserve, organize, create a database of, and make available online every image pertaining to the American Civil War,” according to the initiative’s mission statement on the CCWP website, which includes the following goals:

- A comprehensive digital archive of Civil War images that will include all formats of photography as well as select sketches, drawings, woodcuts and engravings. The emphasis will first be upon Civil War-era documentary imagery but will be designed to expand temporally and spatially to include post-war imagery of battlefields and Civil War sites as well as portrait photography in all formats. The project will expand over time.

- A broad database application that will include at a minimum:

- The ability to organize the database and search by image title, keyword, photographer, studio, location, campaign, date, repository, and more.

- Cross-referencing with contemporary and modern catalogs.

- Thumbnails of each image with direct links to high-resolution files when available.

- An online library of reference materials for Civil War researchers.

- The images will be scanned in high resolution digital format. All backmarks or other identifying information on the images will also be scanned. All imagery will be stored on a computer and backed up on two external hard drives housed in different locations.

- Images will be made available for viewing and, when partnership arrangements allow, for use in published or exhibition materials. Fee structure will be a function of partnership arrangement, but CCWP is committed to making imagery available free or inexpensively.

This project, the Civil War Photography Wiki, will adopt the general intent and aspiration of the CCWP Digital Archive project, in conjunction with the Center for Civil War Photography. The goals stated in the description of that organization’s stalled digital archive take full advantage of the internet’s potential for opening access to the world’s archives, providing the ability to search, view, and download images of historic photographs for research and productive work. The Civil War Photography Wiki differs from CCWP’s original proposal, however, in its open-source, volunteer labor foundation, seeking to foster accurate, transparent, and accessible collaboration in the vein of Wikipedia.

Audience and Reach

The Civil War Photography Wiki will serve as a valuable resource for several constituent groups. First, enthusiasts of Civil War photography, including collectors, hobbyists (alternative process photographers included), museum and archive professionals, and historians are expected to not only use the site but to contribute to it. These highly motivated and educated individuals will be actively courted by the Wikipedian employed by the grant to help populate records and add metadata information to the website. Social media accounts of groups like the Center for Civil War Photography have become invaluable discussion boards for knowledgeable individuals to discover and disseminate new details about Civil War photographs, but this information may be lost if it is not recorded in a more open, searchable, and permanent archive. The Civil War Photography Wiki will harness the collaborative spirit displayed by the community on these sites and in conferences and seminars to crowdsource and maintain a new database of knowledge about these photographs and the topic.

Secondly, the site will serve as an educational and research resource for people seeking visual evidence to investigate the Civil War period. This group of people, perhaps less interested in the history of photography, includes reenactors, historians, and amateur scholars who routinely seek historic photographs as primary sources for their inquiries. Genealogists, too, may perhaps be less interested in the Civil War as a scholarly topic and more motivated to find an image of their ancestors. These users will be encouraged to contribute to the site as well if, for instance, they should be able to identify an individual who has not been previously tagged in a photo, or recognize an unrecorded location, but they will also be able to view and learn from the metadata provided by other users. As will all users of the site, they will also be able to access high resolution image files of any given photograph to research the scene or individual shown, and will learn the location and context of all of the photographic objects in order to continue their research at the given institution.

Another group which the site will target is owners and holders of private Civil War photography collections. They will be able to search the site to identify and authenticate their photographs, and also to post images of their photos for assistance in generating details and metadata. As the site is intended to aspire to a complete database of existing Civil War photographs, the contributions of holders of previously unknown and inaccessible photographs will be welcomed, whatever the motivation. It is assumed that experts in Civil War material culture – uniforms, for instance – will be able to help photograph owners positively date and better understand their photos. If the owners prove unwilling or hesitant to upload high resolution files of their images, exceptions and restrictions on use may be granted for these database entries. Still, however, the Civil War photography community will be the better for its knowledge of the existence of and basic information about these photographs, which may aid scholarship.

Finally, the Civil War Photography Wiki will be a central clearinghouse for images from the Civil War which may be sought by filmmakers, researchers, publishers, and educators as illustrative material. As all of these photographs are out of copyright protection, it is hoped that the existence of this collaborative and educational database will encourage the free flow of information and usage of these photographs, which are sometimes kept behind restrictive institutional or private barriers. As these images have entered the legal public domain, so too should they enter the collective ownership of the American people as part of our shared heritage. So far as possible, contributors will be encourage to upload their image files and contribute information under unrestricted licenses to foster creative and knowledge-seeking fair use.

Partners and Participants

The National Museum of American History will be the principal investigator for this grant and project. The site will be hosted on NMAH servers, maintained by NMAH and Smithsonian New Media and OCIO staff, and the project will receive all other administrative and incidental support from NMAH. The webmaster, likewise, will be a temporary Smithsonian Trust Fund employee working at the National Museum of American History supervised by the Curator of the Photographic History Collection in the Office of Curatorial Affairs.

However, this project is intended as a collaboration between institutional partners with Civil War photographic collections or compatible missions, as well as individuals who will use and contribute to the site.

The Smithsonian Institution has forged a model of interdisciplinary, pan-institutional collaboration in recent years through its Grand Challenges Consortia, an internal granting body which seeks to stimulate intellectual exchange within the Smithsonian and beyond. The group has awarded small Level One and larger Level Two grants to “incubate, develop, and launch collaborations that along with our museums, research centers and programs, address [the Smithsonian’s] Strategic Plan’s four Grand Challenges: Unlocking the Mysteries of the Universe, Understanding and Sustaining a Biodiverse Planet, Valuing World Cultures, and Understanding the American Experience.”

One of the recipients of several Level One and Level Two grants from the Consortia for Understanding the American Experience over the past several years is the Civil War 150 Working Group, comprised of curators, archivists, historians, and other staff from 12 Smithsonian Museums, including the National Museum of American History, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Archives, National Museum of African American History and Culture, American Art Museum, among others. This group has a demonstrated history of success in working collaboratively to increase and diffuse knowledge about and improve access to Civil War collections in the Smithsonian’s museums and research centers. The group conducted a review of Civil War collections across the Institution, organized scholarly symposia on topics in Civil War studies, published a material culture-based book showcasing Civil War collections, Smithsonian Civil War: Inside the National Collection, and contributed to the Civil War 360 series of television programs on the Smithsonian Network.

The group’s latest project has been a comprehensive survey and inventory of Civil War photography collections across the Institution. The culmination of this effort will be the publication of a paper detailing the scope and content of related collections in the Smithsonian’s museums and archives, including information on subject, process, maker, size, condition, and location of every object, and unprecedented pan-institutional inventory. This document will guide not only the further cataologing, care, and digitization of these collections, but will also form the foundation for the collections portion of the Civil War Photography Wiki; the Smithsonian’s Civil War photography objects will be first uploaded and available on the site.

As the webmaster creates the Civil War Photography Wiki, he/she will join the Smithsonian Civil War 150 Working Group, and seek guidance and support from the group for conceptual planning and implementation/creation of the site. Using the Civil War photography survey, existing catalog records, and digital images of Civil War photography collections from all Smithsonian museums, he/she will populate the first set of pages in the Civil War Photography Wiki with metadata and images. The webmaster will continue to work with the guidance and supervision of Smithsonian staff members associated with the Civil War 150 Working Group after the Civil War Photography Wiki is launched.

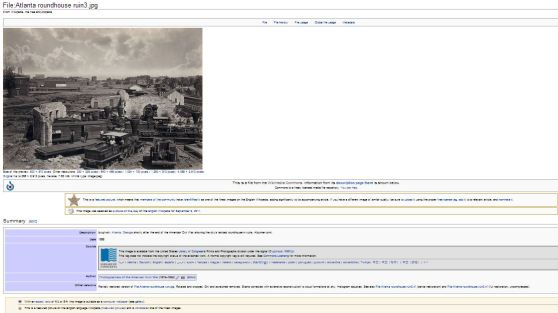

Wikipedia page for George Barnard’s 1866 photograph of the ruins of Atlanta’s railroad roundhouse. This page, populated with information about the maker, date, alternate versions, process, and location of this object in the Library of Congress collections, offers a glimpse of the potential for crowdsourced metadata cataloging and database creation via wiki project.

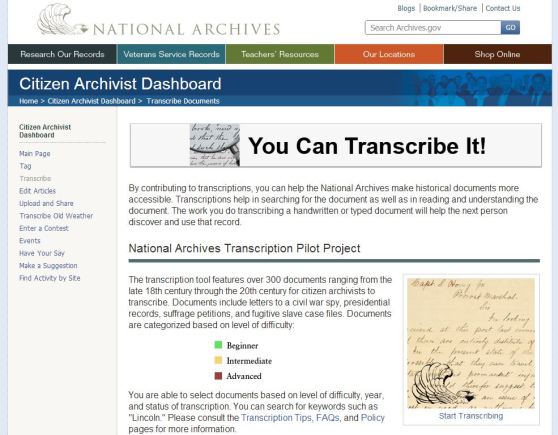

The webmaster will also be tasked with recruiting and managing relationships with and data from institutional partners. Much of the webmaster’s early tenure will be spent working with the following institutions to request portable database records and images of their Civil War photography collections with which to populate the site: Library of Congress, National Archives, Center for Civil War Photography, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Park Service, United States Army Heritage and Education Center, and the Meserve-Kunhardt Foundation. These institutions have already largely digitized and imaged the majority of their Civil War photography collections, and this data will form an invaluable seed and example for other museums and archives to contribute to the site.

The webmaster will also seek advice and support of George Mason University’s Center for History and New Media. The center’s staff, well-versed in the latest scholarship and legal considerations of digital history, will help guide the project philosophically. The center’s digital history fellows will also be asked to assist with technical considerations and be welcomed to help edit and moderate the site.

Budget

The Civil War Photography Wiki will be a very cost-effective project, utilizing the open-source MediaWiki web infrastructure and volunteer labor to create its final product. The team seeks $125,000 to create and implement the site, which will be allocated as follows:

Wikipedian/webmaster= $120,000 (2 years salary at GS-09 Step 1 with benefits)

The Smithsonian Institution has had previous success employing a temporary Wikipedian-in-Residence as its outreach official to the Wikipedia community, digital historian, and editor of Wikipedia entries relevant to the Institution and its mission. The Civil War Photography Wiki will be created, promoted, and maintained for two years by a wikipedian/webmaster with specific technical knowledge of wikis and collaborative online projects, training as a digital historian, interest in Civil War photography, and links to the Civil War community.

Server maintenance costs and administrative overhead

The Smithsonian Institution will be granted $5000 to help cover administrative overhead and server/hosting costs for the site, which will be hosted on the existing NMAH servers.

Implementation/Information architecture

The Civil War Photography Wiki will use the Mediawiki program and wikitext markup language to make it a simple, transparent, and accessible database of information about its titular subject. Mediawiki is a “free server-based software which is licensed under the GNU General Public License (GPL). It’s designed to be run on a large server farm for a website that gets millions of hits per day. MediaWiki is an extremely powerful, scalable software and a feature-rich wiki implementation that uses PHP to process and display data stored in a database, such as MySQL. When a user submits an edit to a page, MediaWiki writes it to the database, but without deleting the previous versions of the page, thus allowing easy reverts in case of vandalism or spamming. MediaWiki can manage image and multimedia files, too, which are stored in the filesystem.”

The Wikipedian will create the site, working with NMAH New Media and Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO) staff to create and host the site, as well as to populate it with well-cataloged data and images of Civil War Photographs from partner institutions. The Wikipedian will then spend the next year promoting the site and recruiting volunteers to help upload and improve data, in essence seeding the community which will help to sustain the site over its useful life. The Wikipedian will be tasked with researching and establishing procedures to moderate and authenticate comments and data entry, including the exclusion of spam and unrelated discussion and contributions. The community on Wikipedia has proven remarkably accurate and quick to purge useless and unsubstantiated information from the entries on that site, as scholar Roy Rosenzweig wrote [“Can History be Open Source? Wikipedia and the Future of the Past,” The Journal of American History Volume 93, Number 1 (June, 2006): 117-46]. It is hoped that within the two years provided for in this project, the community will become self-sustaining and self-policing, and that new information and attributions discovered and shared by users of the site will begin to influence and impact scholarship of Civil War photography.

Evaluation

The Civil War Photography Wiki project will be evaluated on its progress toward the stated mission of creating a comprehensive, accessible, and authoritative database of Civil War photographic collections within 2 years. Among the final tasks of the Wikipedian-in-Residence in his/her tenure at NMAH will be to create a report on the successes and failures of the project. He/she will be tasked with writing detailed responses to each of the stated objectives of the project given the progress of the project over the preceding years. This report will be presented to the Smithsonian’s Civil War 150 Working Group, which will review the project and keep the report on file for future research and potential grant applications to extend funding for the project, as necessary.